Today seven students have come to class and we've finished watching the documentary about Mauthausen. The last part explains what happened when the camp was freed by the USA Army. The prisoners felt that moment as a new beginning, as if a new life started for them. When the USA soldiers took the control of the camp, they discovered thousands of corpses the Nazis didn't have time to burn in the crematories. The prisoners also discovered that, while they had been starving, the warehouses of the camp were full of food. Many former prisoners died of binge eating, because their bodies couldn't assimilate the food, after such a long time of hunger and privation. The USA soldiers helped the prisoners find Ziereis, the commander of the camp, who was shot. Before dying, Ziereis said that he had no responsibility of what had been happening in Mauthausen, because "he only followed orders".

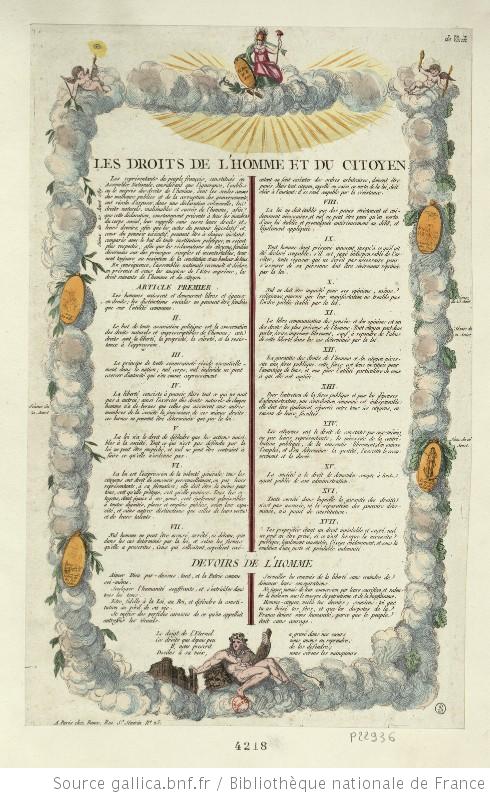

The Spanish prisoners could also recover the photographs Anna Poitner had hidden in her house. Those pictures were decissive for the Nuremberg Trials, where 23 prominent Nazi leaders were judged. Francisco Boix was witness for the prosecution, because the pictures he took showed what had happened in the camp and that many Nazi leaders had visited the camp. His testimony was crucial to condemn Albert Speer and Ernst Kaltenbrunner.

One of the pictures taken by Frabcisco Boix, where Himmler, Kaltenbrunner and Ziereis appeared

After the end of WW2, the Spanish survivors of Mauthausen couldn't come back to Spain. Seven of the men of the documentary settled down in France and Francico Comellas stayed in Austria, very close to Mauthausen. On the 16th May 1945 all the prisoners made an oath to tell the world what had happened there and committed to fight for a new world, free and just. That's why many of them joined associations and participated in conferences and went to schools to tell their story. They felt obliged to remember, to keep the memory of those who had been killed in the camp. The return to the ordinary life wasn't easy. Nightmares with the camp were common and the Spaniards also suffered the exile and oblivion, even when the dictatorship finished in Spain. Their story was ignored by all the democratic governments until very recently. The monument to the 7,000 Spanish prisoners dead in Mauthausen was built with the donations of private people. The first official recognition of the resistance of the Spanish deported was made by president Rodríguez Zapatero in 2005. Zapatero participated in the commemoration of the 65th anniversary of the end of WW2 and visited the camp. Here you have a chronicle of the ceremonies of 2010 and 2013 (this last one, very painful):

The documentary ends with two reflections: Ramón Milà, one of the youngest prisoners, said that humanity hasn't learned from what happened in the camps and similar horrors repeated later and continue to happen. In different parts of the world, people continue to treat their peers as if they were not humans. Finally, Francisco Comellas deposited two stones of the quarry in the memorial dedicated to the Spaniards who died in Mauthausen and remembered that all they went through there had been organized by the Nazis with the cooperation of the Spanish Fascists. The oblivion of the fight of the Spaniards against the Nazis continues to exist.

Drawings made by Ramón Milà

As I said when we started to watch the documentary, only two of the 8 former Mauthausen prisoners who participated in the film are still alive. Both, Ramón Milà and Manuel Alfonso, still live in France. Some of the others, like Josep Egea, Mariano Constante, Antoni Roig and Francisco Batiste, returned to Spain after the end of dictatorship and died here. Some of them wrote about their experiences in Mauthausen or helped to write books about the camp. Here you have a list of these books, just in case you're interested:

- CONSTANTE, Mariano, Los años rojos, Ed. Círculo de lectores, Barcelona, 2005.

- CONSTANTE, Mariano y RAZOLA, M, Triángulo azul. Los republicanos españoles en Mauthausen. Gobierno de Aragón y Amical de Mauthausen, 2008

- TORAN, Rosa,. Joan de Diego: tercer secretari a Mauthausen. Ed. 62, Barcelona, 2007

- ALFONSO ORTELLS, Manuel, De Barcelona a Mauthausen. Diez años de mi vida, (1936-1945), Editorial Memoria Viva, 2007

- BATISTE, Francisco, El sol se extinguió en Mauthausen (Vinarocenses en el infierno), Editorial Antinea, Vinaròs, 1999

- ROIG, Montserrat, Els catalans als camps nazis, Edicions 62, Barcelona,

- BASSA, David y RIBÓ, Jordi, Memòria de l´infern, Edicions 62, Barcelona,.

- TORAN, Rosa, Vida i mort dels republicans als camps nazis, Proa Edicions, Barcelona, 2002

- SERRANO I BLANQUER, David, Les dones als camps nazis, Pòrtic Edicions, Barcelona, 2003

- SERRANO I BLANQUER, David, Un català a Mauthausen. El testimoni de Francesc Comellas, Pòrtic Edicions, Barcelona, 2001

- BERMEJO, Benito, Francisco Boix, el fotógrafo de Mauthausen, RBA Editores, Barcelona, 2002

-WINGEATE PIKE, David, Españoles en el holocausto: vida y muerte de los republicanos en Mauthausen, Ed. Mondadori, Barcelona, 2003

- TORAN, Rosa, Los campos de concentración nazis. Palabras contra el olvido, Ed. Península, Barcelona, 2005

- CONSTANTE, Mariano y RAZOLA, M, Triángulo azul. Los republicanos españoles en Mauthausen. Gobierno de Aragón y Amical de Mauthausen, 2008

- TORAN, Rosa,. Joan de Diego: tercer secretari a Mauthausen. Ed. 62, Barcelona, 2007

- ALFONSO ORTELLS, Manuel, De Barcelona a Mauthausen. Diez años de mi vida, (1936-1945), Editorial Memoria Viva, 2007

- BATISTE, Francisco, El sol se extinguió en Mauthausen (Vinarocenses en el infierno), Editorial Antinea, Vinaròs, 1999

- ROIG, Montserrat, Els catalans als camps nazis, Edicions 62, Barcelona,

- BASSA, David y RIBÓ, Jordi, Memòria de l´infern, Edicions 62, Barcelona,.

- TORAN, Rosa, Vida i mort dels republicans als camps nazis, Proa Edicions, Barcelona, 2002

- SERRANO I BLANQUER, David, Les dones als camps nazis, Pòrtic Edicions, Barcelona, 2003

- SERRANO I BLANQUER, David, Un català a Mauthausen. El testimoni de Francesc Comellas, Pòrtic Edicions, Barcelona, 2001

- BERMEJO, Benito, Francisco Boix, el fotógrafo de Mauthausen, RBA Editores, Barcelona, 2002

-WINGEATE PIKE, David, Españoles en el holocausto: vida y muerte de los republicanos en Mauthausen, Ed. Mondadori, Barcelona, 2003

- TORAN, Rosa, Los campos de concentración nazis. Palabras contra el olvido, Ed. Península, Barcelona, 2005

Many of these books are in Catalan, because many of the survivors of the camps came from this region, The first book to tell the story of the Spaniards in Mauthausen, Els catalans als camps nazis, was written by the journalist Montserrat Roig at the beginning of the 70's. Other historians have continued this work

I also want to recommend you some other books we´ve talked about today. They are very important books, because their authours, who also survived to the Nazi camps, made deep reflections on human nature. They are the following:

- LEVI, Primo, Trilogía de Auschwitz (Si esto es un hombre, La Tregua y Los hundidos y los salvados), Muchnik. El Aleph Editores, 2005

- FRANKL, Viktor, El hombre en busca de sentido, Ed Herder, Madrid, 2004

- FRANKL, Viktor, El hombre en busca de sentido, Ed Herder, Madrid, 2004

I would also like to say that it has been a real pleasure for me to spend almost 3 hours with you today, talking about so many interesting things. I wish we could repeat this soon.